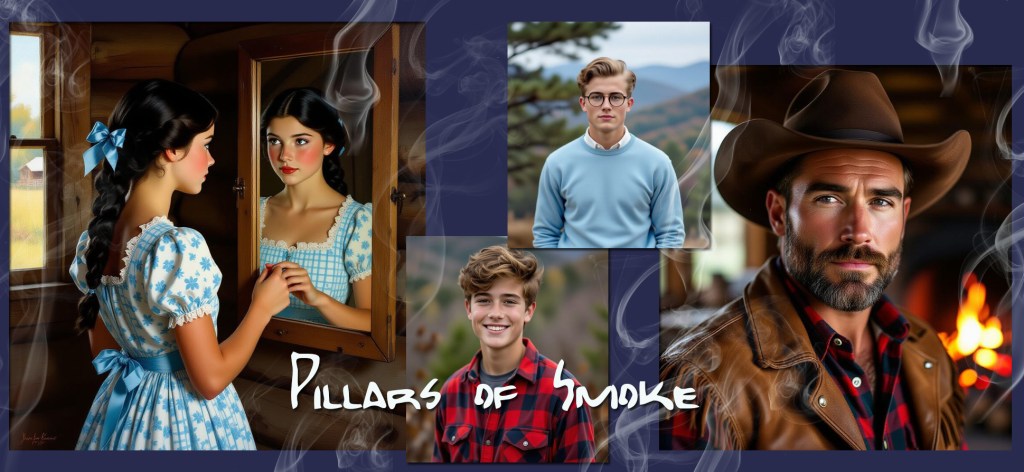

A Novel of the Ozark Mountains

Susannah Jarvis was a pretty, fun-loving, headstrong girl from the Ozark Mountains. One day her life started to change when the big, hearty Chastain family came to live nearby. She was courted both by the serious, poetry-loving Clovis and his flighty, mischievous younger brother Billy. And Susy’s brother Randy was completely captivated by the beautiful and bewitching Fair-Ellen. Then, seemingly from out of nowhere, came a dark and mysterious man, Shad Hewitt, who was fatally drawn to Susy. The Chastains had once been involved in a blood feud with the Hewitts. Would Susy’s attraction to Shad re-kindle the spark of the long-dormant family war? And will she be able to resist his enigmatic charm? A bittersweet novel about our choices and their consequences, with elements of romance, regional, humor, gothic, and mystery combined into one.

Excerpt:

“My granny on my ma’s side was a real heller,” Susy mused. “One time when Grandpa made her mad, she up and bit a chunk out of the kitchen table.”

“Did she?” Fair-Ellen laughed.

“Well, Grandpa said she did,” Susy laughed too. “And he showed me the table with the chunk missin’. And you won’t believe what song she wanted sung on her deathbed.”

“The one that goes ‘I’m gonna eat at the Master’s table/Down by the riverside’?” Fair-Ellen said.

Susy doubled over with laughter. Fair-Ellen joined her. Ben and the boys turned to look. Fair-Ellen waved at them. Randy turned back to look at her again until he stumbled over something in the road.

“What song was it?” Fair-Ellen asked, when they could get their breaths.

“Well,” Susy said, “right at the last, Aint Fern was looking after her, and one day Granny said she was a dying, and Aint Fern says, ‘Oh Ma, you want me to go for the pastor?’ And Granny says, ‘Sweet Jesus, no, chile, I don’t want that ole gasbag at my deathbed. I jist want somebody to sing me a li’l song.’ And Aint Fern says, ‘Which one, Ma? In the Sweet Bye and Bye, or’— ‘Sweet Jesus, no, child,’ Granny says. ‘Rye Straw’ is the one I’m a wanting.’ ‘Rye Straw’? You shore, Ma?’ ‘Yes, child,’ Granny says like butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth. You know that song, Fair-Ellen?”

“Cain’t say’s I do,” Fair-Ellen said.

“It ain’t very nice,” Susy warned her. Then folding her hands primly in her lap, she sang:

Dog shit a rye straw

Sheep shit a fiddle bow

Cow tore her butt off

Trying to shit a grubbin hoe…

“Oh lordy,” gasped Fair-Ellen, and the two girls laughed till they cried.

****

For a long time Susy lay staring at the full moon that looked through her window at her. Suddenly she sprung out of bed, lit a candle, then tiptoed to the loft ladder. Gripping the front of her nighty in her teeth, she climbed the ladder as best as she could with one hand, holding the candle aloft with the other. Then she set the candle holder on the loft floor, raised herself up and looked around. Dried apples hung in festoons from the rafters, dried peppers and herbs dangling like vines all around. Corn hung in bunches, black and yellow grains looking like bad teeth grinning in the candlelight. Ah, there was Randy’s old raggedy shirt hanging on a nail. Too bad he didn’t leave a lock of his hair behind too….

Sitting on the edge of her bed, she took the candle and began dripping wax into the dish until it formed a big warm lump. Before it had a chance to harden, she began molding it with her fingers into the shape of a tiny head. Then she dripped more wax to form a crude torso, then arms and legs. When the poppet was finished, she found her patchwork scissors and fell to snipping at Randy’s shirt, fashioning a rough little garment. With this she dressed the wax figure she had made.

Hixamus hexamus hoxy poxy, dillymus dallymus dixy doxy….She took a long fancywork needle from her pincushion and held it poised above the poppet…. But why wouldn’t her hand move? She could see the full moon, with clouds moving past like the spirits of sheep on their way to a heavenly pasture. Somebody said the man in the moon was Cain holding a thorny bush. Now he was a telling her: Don’t do what I done. He’s your brother…your brother…your brother…. Glancing up at the little mirror, she saw her own face, white and full of ghosty shadows in the candlelight, like a small moon of itself against the blackness of her hair, the eyes dark-wild like two little thorny bushes. The needle quivered like a compass needle, pointing downwards, in the direction she surely was headed….

“I cain’t do it,” she said to the moon, laying down the needle. “I hate him, but I cain’t do this, not even for Fair-Ellen.”

And making her way to the window, she parted the curtains and pitched the poppet out into the garden, where it landed staring eyeless up at the moon through the sweet-tater leaves.

****

Suddenly somebody crashed into her from behind, knocking her clear over. A young man fell over along with her. He gawked stupidly at her, then without even stooping to help her up, he rose and stumbled off, hiccuping, leaving her sprawled on the floor.

“Mister, I believe in these here hills when a feller knocks a lady over, he stops to pick her up and put her on her feet again,” a soft-spoken voice said. Susy felt hands grasp her by the waist the way you might lift a lamb and raise her to her feet. She didn’t even have to look to see who it was. “Ye all right?” the dark man asked her in a pleasing baritone that had a faint note of sadness in it.

“Um…I reckon…” Susy clutched at his arm. Her hair hung half over her face—the ribbon must have come out. Had he been watching her all this time? He had a shapely mouth under the mustache and a good chin, what she could see of it through the well-trimmed beard. His eyes were sad, but with deep lights in them like far-off planets.

The musicianers were playing “Black Hawk Waltz,” a slow and plaintive tune that put down some of the racket. The man looked at Susy with his mouth moving, and she barely heard what he said. But she knew he was asking her to dance. He turned out to be a pretty fair dancer, moving nice and easy. There was a wild splendor about him, like an eagle that belonged to the mountain fastness and the west-burning sun. When he told her his name it hardly registered with her at first.

Shad Hewitt. It rang a bell, but she couldn’t place it.

“Be ye alone, little gal?” he asked her with that electrifying smile.

I…I’m with Patty Jenkins,” she said glancing about for Patty, and she saw her friend looking at her with lifted eyebrows. “There she is with Leroy Haskell.”

“You want something to drink?” he asked her almost shyly when the music ended. She nodded. “Set you down here and I’ll be back in a shake.”

She watched him move toward the table. I’d ort to give him the slip, she thought all the while knowing she wasn’t going to do it. Soon he returned with a Dixie cup, smiling.

“There was factually some cold water,” he said. She sipped at the cup like it was honey dew and milk of paradise like in a poem Clovis had read her. “You feel like dancing ary more?”

The band had struck up “Lost Injin” a peculiarly rousing tune that summoned up something hidden and primitive in Susy, so that she boldly held out her arms and they danced with their eyes locked, feet tracing ancestral paths, stirring the dust of sleeping, sleeping days, whirling and stomping, pursuing and reversing, a journey from which she would never return. When the music ended she felt a divine exhaustion like a sacrificial virgin closing her eyes in sanctified death. Shad fanned her with the paper fan from Seeley’s Undertaking Parlor like a slave fanning a princess in the movie pictures.

Shutting her eyes, she could see fireworks of incredible brilliance. Skyflowers blooming and shattering in sped-up time, phoenix birds of green and gold and scarlet rebirth….

Then there was a shout, and her eyes popped open and the fireworks vanished.

Home